Born in Kansas in 1900, Barbara Morgan

moved with her family to a peach farm in Southern California where she spent

her youth. During this time, Morgan developed an early interest in dance

and movement. Her father noted this interest and suggested that the five-year-old

“think of everything in the world as dancing atoms.”[1]

Since that young age, Morgan examined the world and her artwork with this

scientific perspective.

This mindset was further affirmed during Morgan’s

formal training at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1923. Under

the direction and principles of Arthur Wesley Dow, Morgan explored the concept

of art synthesis, which paired abstract design with figurative drawing and

painting.[2]

These principles are evident in Morgan’s early work, which consisted mostly of

drawings, prints, and watercolors. She was

also influenced by the “Chinese Six Canons of Painting,” which were developed

by art historian, Xie He, in sixth-century China. According to He, there were six points to

consider when examining a painting: spirit resonance, bone method,

correspondence to the object, suitability to type, division and planning, and

transmission by copying.[3]

Morgan specifically appreciated the concept of spirit resonance, which refers

to the vitality and nervous energy transmitted from the artist into the work. This

energy contributes to the overall power of a work of art. He contested that

without spirit resonance, there was no need to look further into an artwork.

Morgan felt similarly and found that spirit resonance encapsulated her father’s

early suggestion on how the world and beauty was composed.

Morgan found that she could incorporate

spirit resonance into her work through lighting and balance. While at UCLA,

Morgan volunteered to set up stage lighting for a group of visiting French

playwrights. The playwrights staged and performed Failures, a play that traced emotional changes over time. Morgan

was tasked with constantly changing the mood on stage through the lighting. Since

Morgan possessed no training in theatre or lighting, much of her learning

occurred on site. Despite this lack of knowledge, Morgan became fascinated by

lighting principles and was able to master them in a short time. The experience

taught her about the overall power and role lighting plays in bestowing meaning

to an artwork.

Morgan experienced a shift in her career

after working with her husband, Willard D. Morgan, on a photo project of Dr.

Albert Barnes’ art collection in Merion, Pennsylvania. At the time, Morgan did

not consider herself a photographer; however, she used the project to explore

photographic lighting. As part of the project, Morgan was allowed to photograph

Barnes’ entire collection. While photographing a fertility sculpture from Sudan

and masks from the Ivory Coast, she discovered how these ritual sculptures

became either menacing or benign, through control of lighting.[4]

This revelation further confirmed Morgan’s belief in the power of lighting and

shifted her interests to photography. In fact, light manipulation became the

central theme in her famous photographs of American modern dance and movement.

In Morgan’s photographs of dance and

dancers, she attempted to free figures within space, focusing on singular

movements and light in order to create a slow-motion effect. Morgan stated, “I

love to build a lighting scheme in which light and the moving subject matter is

reciprocally alive; now moving in opposition, by-passing, flowing together,

modulating into shadow, reappearing in muted areas, until the entire design is

rich and mobile.”[5] Morgan’s

passion for lighting schemes is prominent in her Sixteen Dances series. For this series, she collaborated with

Martha Graham, a modern dancer and choreographer, and her company.

|

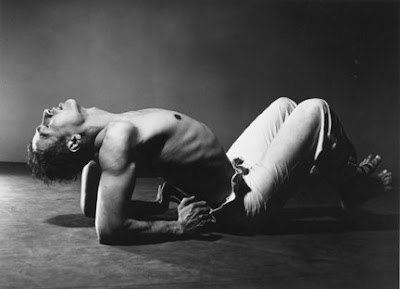

| Barbara Morgan, Jose Limon-Mexican Suite-Peon-1944, 1944, printed c. 1980, silver print. Gift of Gary Granoff, Esq., 1983. |

Sixteen

Dances is an important

series in Morgan’s career because it showcases the purpose and artistry behind

her craft. Morgan shot all of the photographs in Sixteen Dances in her studio with specific lighting that she

designed for each piece. Thus, the project was challenging from a technical

point of view and put insurmountable pressure on Graham and her company. Due to

the technicality of Morgan’s process, Graham and her dancers were often asked

to pose and re-pose countless times in order to achieve the proper lighting and

perspective. Reflecting on the experience, Graham remarked in an interview

that, “[Morgan] was a terror.”[6]

However, it is important to note that Morgan’s specificity during the project

was necessary in order to transfuse spirit resonance into each piece. Morgan

remarked on this necessity, stating, “I wanted to show that Martha had her own

vision. That what she was conveying was deeper than ego, deeper than baloney.

Dance has to go beyond theater....I was trying to connect her spirit with the

viewer—to show pictures of spiritual energy.”[7]

Ultimately, in the series, Graham’s energy is successfully conveyed as a fluid

and significant movement, which the viewer can experience without having knowledge

of the entire dance.

Capturing the beauty and effort of dance

on film takes not only a trained eye, but, more importantly, an understanding

of the science that creates such action. Barbara Morgan mastered both of these

abilities. Her legacy of observing life in relation to “dancing atoms” will always

be preserved on film and on paper, providing a glimpse into her world of

photography, light and modern dance.

Barbara Morgan’s works will be on display

as a part of The Other 90%: Works

from the GW Permanent Collection, on view until June 3, 2016 at

the Luther W. Brady Art Gallery.

[1] Dunning,

J. (1992, August 19). Barbara Morgan, Photographer Of Modern Dance, Is Dead at

92. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1992/08/19/arts/

barbara-morgan-photographer-of-modern-dance-is-dead-at-92.html

[2] Knappe, B. (2008). Barbara

Morgan’s Photographic Interpretation of American Culture, 1935-1980.

[3] Cahill, J. F.. (1961). The Six Laws and How to

Read Them. Ars Orientalis, 4, 372–381. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4629151

[4] Knappe, B. (2008). Barbara

Morgan’s Photographic Interpretation of American Culture, 1935-1980.

[5] Morgan, “Kinetic Design

in Photography,” 27.

[6] Acocella, J. (2011, June

1). An Unforgettable Photo of Martha Graham. Smithsonian Magazine.