Brigham’s work introduces new and provocative perspectives to the feminist art genre. Like fellow female artists of her generation, Brigham draws upon portraiture, a powerful and historical medium, in order to incorporate an analytical and historical lens in her work .[i] Brigham’s work literally encompasses her personality and self. Her face makes up the model faces in her series of portraits that depict female artists like Frida Kahlo, Élizabeth Vigée- LeBrun, and Artemisia Gentileschi. This infusion of self-identity with another form of identity is the intriguing thesis empowering Brigham’s work. Her pieces are a resurrection of the past and commentary on the present. By drawing on art history to form the foundation of her pieces, Brigham essentially calls these female subjects back to life in order to study their lives in relation to the present. Ultimately, Brigham’s work reveals an emotional examination of herself and her predecessors that is hauntingly beautiful and poignantly deep.

Choice, construction, and execution of Brigham’s subjects are dynamically resonating for the viewer. Brigham is not afraid to revive a subject like Frida Kahlo, who notably suffered severe emotional and physical pain throughout her life and art career. In fact, Freeing the Frieda in Me, 2003 incorporates the elements of Kahlo’s lived reality, while also bordering on the brink of topics concerning mortality and death. When Brigham began work on Freeing the Frieda in Me, her father had just passed away. Therefore, Brigham’s attraction to Kahlo is evident. Frida, like Brigham, uses herself as subject for her work. Kahlo lived a life that was delicately balanced on the lines of death. She experienced intensive physical agony and personal pain that made her sensitively aware of the fragility of her being and life. Her self-portraits became a consistent and grounding part of her life when she was left immobile for three months after a bus accident. Upon reflecting on this time, Frida Kahlo once said, "I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best.”[ii] Thus, upon using herself as a subject, Kahlo recognized the mixed fragments of depression, self-hate, and resiliency in herself, which were expressed through her symbolic style. Often, this style resulted in whimsical and dreamlike works, yet Kahlo insists that her works were not products of dreams, but only of reality, refusing to ever compromise the two. Ultimately, by fusing with Kahlo in this piece, Brigham enabled herself time to think profoundly about death through the spirit of Kahlo, allowing her the same experience of self-acceptance that Kahlo endured as she contemplated death.

Similar to Kahlo, Élizabeth Vigée-LeBrun believed that painting and living were one in the same. LeBrun is one of the best-known and most fashionable portraitists of 18th century France. Her style of loose brushstrokes and fresh tonalities drew sitters from the aristocracy and the royal court. Her flattering and graceful depictions of her sitters eventually gained the interest of Marie Antoinette, who became the subject of over a thirty of Le Brun’s portraits. In Brigham’s piece Elizabeth and Julie as Juno and Flora, 2011 the ideas of motherhood and artistry are explored through LeBrun’s relationship with her daughter. Brigham emulates LeBrun and her daughter in the piece by interweaving her own daughter’s face into the secondary subject. Brigham’s depiction of her motherhood is evocative for viewers, who are allowed into such an intimate setting. Additionally, it is revealing of a maternal side that isn’t always displayed by female artists, who juggle motherhood with artistry. Symbolically, Brigham includes a single butterfly into the piece to represent rebirth and regeneration. This is meaningful because it alludes to both the continuation of LeBrun’s legacy by Brigham and the possibility for further continuation by Brigham’s daughter.

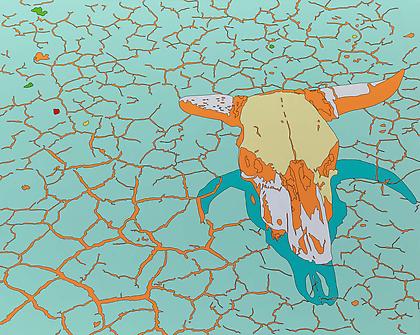

Holly Trostle Brigham, Artemesia: Blood for Blood, 2000 Holly Trostle Brigham, Freeing the Frieda in Me, 2003

Similar to Kahlo, Élizabeth Vigée-LeBrun believed that painting and living were one in the same. LeBrun is one of the best-known and most fashionable portraitists of 18th century France. Her style of loose brushstrokes and fresh tonalities drew sitters from the aristocracy and the royal court. Her flattering and graceful depictions of her sitters eventually gained the interest of Marie Antoinette, who became the subject of over a thirty of Le Brun’s portraits. In Brigham’s piece Elizabeth and Julie as Juno and Flora, 2011 the ideas of motherhood and artistry are explored through LeBrun’s relationship with her daughter. Brigham emulates LeBrun and her daughter in the piece by interweaving her own daughter’s face into the secondary subject. Brigham’s depiction of her motherhood is evocative for viewers, who are allowed into such an intimate setting. Additionally, it is revealing of a maternal side that isn’t always displayed by female artists, who juggle motherhood with artistry. Symbolically, Brigham includes a single butterfly into the piece to represent rebirth and regeneration. This is meaningful because it alludes to both the continuation of LeBrun’s legacy by Brigham and the possibility for further continuation by Brigham’s daughter.

The theme of legacy was

previously explored by Brigham in her work Artemisia:

Blood for Blood, 2000, which explores the impact of Artemisia Gentileschi’s artwork

after enduring a violent and publicized rape. Gentileschi, an Italian Baroque

painter, produced artwork during an era that discouraged the motivations of

female painters. Yet, Gentileschi surpassed these societal constructs and

eventually became one of the most accomplished artists of that time. In Brigham’s

painting, she depicts the moment that immediately follows Gentileschi’s rape,

showing the insurmountable tension of the scene and its uncertainty. Feminist

studies of Gentileschi’s work note a conscious impact the rape served in her artwork,

which is expressed through primary and empowering female subjects.[iii] The unfortunate event of Gentileschi’s rape often overshadows the context and

interpretations of her artwork and alters her legacy. Gentileschi, undoubtedly

was a victim of a violent injustice, however; she is not victim when she

paints. Rather, she is revolutionary and didactic because she employs artistic

qualities that were believed to be incapable for female painters of her time to

grasp. Thus, Brigham’s choice in subject is quite resonating for modern female

viewers of her work who struggle to ascertain power in the disadvantage of

their positions. Ultimately, Brigham shows that it is through these positions

that women can create the most powerful revelations for its society.

Brigham’s

practice and work are thoughtful embodiments of her feminist character. Every

piece is an opportunity for Brigham to explore herself through the contexts of

other female artists, illustrating an ongoing need to challenge her perceptions

and perspectives. Thus, her work never falters because of its urgency and

meaningfulness. Her upcoming exhibition at the Luther W. Brady Art Gallery will

surely offer equal insight and provocation similar to how the works of her

muses did so in the past. Dis/Guise will be on view in the coming new year

starting on January 15th.

[i

Fortune,

Brandon Brame. Portraiture as Feminist History: Holly Trostle Brigham's

Pantheon. Print. (Exhibition catalogue- introduction)

[ii"Frida Kahlo Biography."

Frida Kahlo: The Complete Works. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Nov. 2013.

<http://www.frida-kahlo-foundation.org/biography.html>.

[iii] Pollock,

Griselda. "Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian

Baroque Art."

The Art Bulletin 92.3 (1990): 499-504.

College Art Association. Web. 20 Nov. 2013.

<http://www.collegeart.org/pdf/artbulletin/Art%20Bulletin%20Vol%2072%20Vol%203%20Pollock.pdf>.